Photo credit: Nathea Lee

(Video courtesy of Blossom Productions)

WHERE HEAVEN’S DEW DIVIDES

Where Heaven’s Dew Divides is a collage of artistic impressions inspired by events and personalities that launched the African American Church movement at the turn of the 19th Century and were powerful forces for religious, social, and political change in Philadelphia and beyond. The dance and music that comprise this production represents the ways that artists of diverse backgrounds, genres, and styles are stimulated and moved by the struggle, passions, resilience, and persistence of African Americans who challenged racial and gender barriers and conventions and fueled the fight for racial dignity, self-determination, and justice.

Historical Events and Personalities

Where Heaven’s Dew Divides began as a question about the inner lives of the enslaved African Americans who served George and Martha Washington at the President’s House, America’s first “white house”. What events might have captured the minds and hearts of Ona “Oney” Judge, Hercules, Moll, Joe Richardson, and the rest of the nine enslaved black servants when they were transported from Washington’s plantation in rural Virginia to Philadelphia, the nation’s bustling capital, and home of more than 2000 free black people? No doubt, the news of the revolution in San Domingo (Haiti) excited and inspired people who imagined what it would take to gain their own freedom. But only blocks from the President’s House other powerful and inspiring forces were gathering in the founding of an independent black church movement by former slaves Richard Allen and Absalom Jones.

In 1787, frustrated by discrimination and segregation in white-controlled religious communities, Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and other black worshipers walked out of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia after being pulled from their knees as they prayed in a gallery that was closed to blacks. (Some historians place this event in 1792.) According to Allen, Jones protested the attempts of a white trustee to eject them by saying “Wait until the prayer is over, and I will get up and trouble you no more.” Already convinced that a separate black church was necessary for the spiritual and social advancement of former slaves, Jones and Allen resolved to establish their own church, and led the way for St. Thomas’s African Episcopal Church and Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church to open their doors in 1794. Historian Gary Nash asserts that the independent black church movement “represented the growing self-confidence and determination of the free blacks of Philadelphia”…and that “these two black churches became the most important instruments for furthering the social and psychological liberation of recently freed slaves.”

Less than a year before Bethel and St. Thomas’ held inaugural services, Jones and Allen organized a civic-minded campaign to tend to the sick and bury the dead in the worst outbreak of Yellow Fever in North America’s history. Out of a population of 45,000, 5000 Philadelphians died and an estimated 17,000 fled. As the fever depopulated the city, physician and Declaration of Independence signer Benjamin Rush appealed to Jones and Allen to enlist members of the African Society to nurse patients and carry coffins. From September to November 1793, a contingent of black men and women visited hundreds of yellow fever victims and their families, nursed patients mad with fever and covered in blood, attended to the sick and dying for days at a time, and carried the coffins of the dead. Contrary to Rush’s belief that blacks were immune to the disease, blacks succumbed at about the same rates as whites. When their humanitarian efforts were scorned in the white press as profiteering and extortionist, Jones and Allen published their own account of black people’s service and sacrifice during the epidemic.

Women played a crucial role in founding and sustaining the African Methodist Church, even though official leadership roles were denied them. A dozen or more women were active in the movement-building work following the walk-out from St. George’s Church. Richard Allen’s first wife, Flora, was a devoted helpmate, and shared Allen’s commitment to an independent black church and community uplift. Sara Bass Allen, Richard Allen’s second wife (after Flora’s death), exercised her influence as “mother” of the church to provide proper attire for the pastors as the denomination grew, organize church conventions, and administer Bethel’s missionary and humanitarian work. The black Methodist church, unlike its white counterpart, allowed women to preach from the pulpit, but not without a struggle. Jarena Lee, who felt called to preach in 1807 at age 24, battled a decade of exclusion before Richard Allen licensed her as a preacher around 1817. Her spiritual autobiography, self-published in 1836, is a vivid account of her conversion and zealous pursuit of the ministry.

Themes that emerged in the course of the artists’ research and exploration, and that influence the shape and content of the performances include the persistence of African American religious leaders of the era; the role of publication, especially the spiritual autobiography, in promoting self-determination and dignity for free black people in 18th/19th Century Philadelphia; the role of women in the black church movement; and the choreography of activism over generations.

Collaboration and Improvisation

Improvisation is a principal expressive vehicle for this production. Improvised movement, music, and vocalization were the building blocks for developing the structure of the pieces that comprise the production; and improvisation is used throughout the performances. The performances are structured to allow the artists to respond in the moment to inspirations coming from the environment, the audience, and from each other.

Heaven’s Dew is the product of a process of close collaboration among eleven artists. Each part of the production is co-created by two or more of the following cast:

Adrienne Abdus-Salaam: African/Afro-Caribbean Dancer

Dave Burrell: Internationally renowned composer, pianist and improviser

Ellen Gerdes: Modern and Chinese traditional dancer, vocalist

Germaine Ingram: Choreographer, percussive dancer, vocal improviser

Corinne Karon: Choreographer, percussive dancer

JungWoong Kim: Choreographer, modern dancer

Diane Monroe: Composer, violinist and improviser

Khalil Munir: Percussive dancer, Actor

Kristin Shahverdian: Choreographer, modern dancer

Leah Stein: Choreographer, modern/site-specific dancer

Sheila Zagar: Choreographer, modern dancer

Concept and Direction: Germaine Ingram and Leah Stein

Design and Production:

Lighting Design and Technical Direction: Leigh Mumford

Costume Design and Fabrication: Katie Coble

Visual Media Consultant: Jorge Cousineau

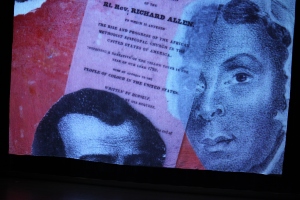

Artist Image: Theodore A. Harris (with Germaine Ingram), The Struggle for Heaven on Earth, mixed media collage on paper, 2013. Collection of the artist

Acknowledgements:

Our deep gratitude goes to:

PIFA administration and staff

The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, and the Wyncote Foundation for their support of the exploratory and creative process for this production.

The Library Company of Philadelphia for archival images

Emmanuelle Delpech, Shavon Norris, Viji Rao, and Robyn Watson for guidance and encouragement

Leah Stein Dance Company